Vox Feminae

Abbaye de Fontevraud | Fontevraud Abbey

Image 1: Portrait of Eleanor of Brittany, from the collection of Fontevraud Abbey. Image 2: Fontevraud Abbey c.1699, from the collection of Fontevraud Abbey. Image 3: Exterior of Grand Moûtier. Image 4: Stone Effigy of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Image 5: Mirabilia (2020) by artist François Réau. Image 6: The Abbey crypt with media projection by artist Eve Deroeck.

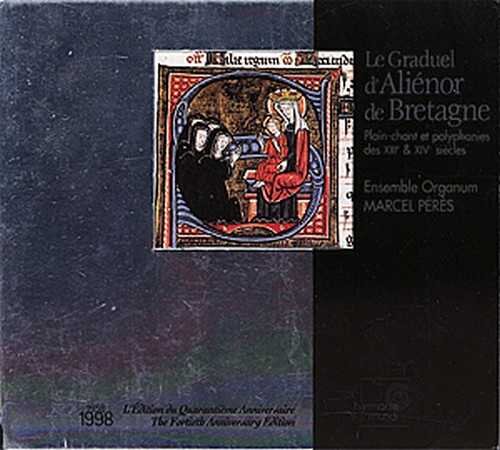

This chant is from the Graduel d’Alienor, a thirteenth-century liturgical songbook commissioned for Eleanor of Brittany, the sixteenth Abbess of Fontevraud. Eleanor was the sixteenth of thirty-six women who would lead the monastic city in a lineage that endured for over seven hundred years. The center of Fontevraud is the Abbey of Grand-Moûtier, which still stands at the edge of a small village in western France, the double spires of its facade reaching up into the open sky of the Loire Valley.

Today, this site of centuries of prayer and meditation is home to another kind of devotional practice: the creation and exhibition of art. But before we explore Fontevraud’s current incarnation, we need to go back to the beginning, to the early twelfth century, and a wide, wild landscape.

It was in the valley of Fons Ebraldi that a charismatic wandering preacher named Robert d’Arbrissel first led his followers into the woods to live in hermetic tradition. Their first temple—a cathedral of trees, where they prier sous les nuages, pray under the clouds, a sanctuary previously only consecrated by the language of birds.

The light shouts in your tree-top, and the face

of all things becomes radiant, and vain;

only at dusk do they find you again.

The twilight hour, the tenderness of space,

lays on a thousand heads a thousand hands,

and strangeness grows devout where they have lain.

- Rilke, Book of Hours

In 1101, d’Arbrissel formally founded the order of Fontevraud, a double order of both men and women. It was also a Marian order, devoted to the Virgin Mary and her spiritual motherhood. As such, d’Arbrissel established that it would be led, for all time, by a woman. There were other double orders at the time, but as medieval scholar Berenice Kerr writes of Fontevraud, “Its structure represented a unique solution to the question of how best to serve the spiritual and material needs of women striving to follow a monastic vocation. The position of both the men and the women was carefully defined,” contrasting with other situations “where the nuns were simply attached…to a male structure.” And as the twentieth-century Abbot Joseph Pohu writes, “The abbess took orders from none but the pope in spiritual matters and from the French king in temporal affairs.”

The very first stone of the great Abbey was laid in 1104. It was completed in 1150—an extraordinary example of Romanesque ecclesiastical architecture: ascendant arches of cream-white Tuffeau stone, a columned nave, and a choir that extended into the adjacent cloister, chapterhouse, refectory, and beyond, home to the community of monastic women.

“You have to imagine as well, that they were wandering in the galleries of the cloister, that their steps would be echoing under the vaults because everything there is in Tuffeau stone.” Zoé Wozniak, a cultural mediator at Fontevraud. “No wood, no tapestries, nothing to… the sound would rebound on all the walls all the time. Many, many staircases as well. The doors would be opened everywhere in this monastery because when you are in a cloister, it's the really center of the monastery. So wherever you want to go, you have to pass through the cloister, meaning that the nuns would cross this central garden twenty-five times a day, probably, to go to the refectory, to the chapter house, to church, to the dormitory. So this was really the center of the activity.”

The Fontevristes were a Benedictine order, following the monastic law established by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century. They lived by the Divine Office, or the Liturgy of the Hours—the days divided into prayer, work, and study. The bell called them to pray and sing eight times each day, including at midnight for Night Watch and at sunset for Vespers, or the Lighting of the Lamps.

“They lived by the Divine Office, or the Liturgy of the Hours—the days divided into prayer, work, and study. The bell called them to pray and sing eight times each day, including at midnight for Night Watch and at sunset for Vespers, or the Lighting of the Lamps.”

Zoé Wozniak (ZW): “Their life was organized very, very regularly, meaning that every day was the same. And this lasted for years because when they entered the Abbey, there were sometimes seven years old, and they stayed there until they died. So basically twenty-four hours a day, divided into three parts: eight hours, as I said, for praying, so meaning that at midnight, there were all asleep in their dormitories, the bell is ringing, they should go down the cloister, cross it to join the church for the first service of the day.”

And overseeing it all was the abbess who was responsible for a monastic city which at its height was home to three thousand nuns and monks. She was often drawn from the French nobility, because as a royal householder she would have experience in managing a large estate, and be literate as well. One of the most extraordinary of the abbesses was Gabrielle de Rochechouart: daughter of a French Duke, older sister of the Marquise de Montespan, and appointed by Louis the XIV as Abbess and Superior General of the entire order of Fontevraud.

ZW: “She is really one of the major figures talking about the abbesses of Fontevraud. She is the thirty-fourth Abbess of Fontevraud. So we are here in the seventeenth century and Louis the XIV is the Sun King of Versailles, and Fontevraud is part of that. Even if it's an abbey, even if it's enclosed in big, thick walls, it is very political. So the abbess goes to Versailles every so often to deal with the king and with lords, etcetera. Because Fontevraud was the most powerful order of France at that time.”

Gabrielle cultivated an intellectual and artistic culture at the Abbey. Fluent in multiple languages, a translator of Homer and Plato, and friend of many artists and writers of the day, she welcomed Jean Racine to Fontevraud in 1689, where his play, Esther, was performed by Gabrielle and the nuns. Abbess of Fontevraud for over thirty years, from 1670 to her death in 1704, Gabrielle, for her exceptional mind and her dedicated leadership, was known as the “Queen of the Abbesses.”

But five hundred years before Gabrielle was Eleanor of Aquitaine, who lived from 1122 to 1204, and was one of the most powerful women of the medieval age, reigning as both Queen of France and Queen of England. She herself was not an abbess or a nun at Fontevraud, but her legacy is deeply intertwined with the monastery—as a Plantagenet, as a patron, as a resident for the final years of her life, and as grandmother of its sixteenth Abbess, Eleanor of Brittany, whose songbook we heard at the beginning of the episode.

ZW: “She is linked to Fontevraud by the end of life. Since then, we know that Eleanor came every so often to Fontevraud, probably to visit the tombs of her husband and favorite son. And finally, Eleanor died in Poitiers in 1204, eighty-two years old, and she asked to be buried in Fontevraud as well.”

One of Eleanor's artistic legacies is her commission of the iconic effigies of Fontevraud, four recumbent figures that lie in the nave of the church.

ZW: “Well they are the most important artifacts that one can see visiting Fontevraud because there are four recumbent statues of these major kings and queens that were the Plantagenets: Eleanor herself, Henry II Plantagenet, Richard the Lionhearted, and Isabella of Angoulême, who was John Lachlan—King John’s—wife, so she was Queen of England as well. Well, the point of a recumbent statue is to cover the sarcophagi, if you want, so it's a representation, an idealized representation, of the person who was supposed to be buried underneath. So they are represented quite young with all the symbols of a king or queen. So the crowns, scepters, swords, etcetera. So they're quite interesting in terms of their history of art references.”

Eleanor's effigy holds a book, positioning her as eternally engaged in whichever text we might imagine she is holding before her.

ZW: “She, well we know that she commissioned the recumbent statues, so she obviously was the one who decided to wear a book on her hands. It is one of the first recumbent statues in the history of art who is active, and when she is reading, it means that she is still living, she's still alive, and in stone. So, symbolically, it means that she is still alive, forever. So clever of her.”

Eleanor could be reading a letter from her contemporary, the great Benedictine abbess, mystic, and composer, Hildegard of Bingen, whose monophonic piece, “Voice of the Living Light,” you're hearing now. Eleanor wrote to her for counsel; Hildegard responded with this:

“Your mind is like a wall, which is covered with clouds, and you look everywhere, but have no rest. Flee this, and attain stability with God.”

The great succession of abbesses at Fontevraud continued until the late eighteenth century, when, during the French Revolution, it was seized and disestablished as a monastery. Under Napoleonic rule, the Abbey became a prison and remained as such for the next 150 years.

In 1975, it began its new life as a center for art and culture. The priory, cloister, and garden once again activated by poetry, music, and art. But one of its first projects was not of creation, but of excavation. Deep beneath the foundation of Grand Moûtier, the earth still held a thousand years of history. An archaeological excavation seeking the Plantagenet necropolis brought ancient spaces of the Abbey to light, including a twelfth-century crypt; the caveau, or Vault of the Abbesses; and the empty tomb of Robert d’Arbrissel.

ZW: “We don't know but it is possible that things were stolen, destroyed or sold. But there are relics of Robert d’Arbrissel. There are reliquaries, small reliquaries containing powders and dust from his heart…”

Mirabilia is Latin for “wonder” or “marvel.” And in summer 2020 there was one to be seen at Fontevraud. In the choir of the Abbey, contemporary artist François Réau created an installation speaking to the spirit and history of place: a monumental cumulus cloud—hand-drawn in graphite—star charts of the twelfth-century sky, and a dense field of dried vines encircling the choir and enveloping at its center an illuminated book, like the one held by the effigy of Eleanor. We spoke to François about his work.

“A monumental cumulus cloud—hand-drawn in graphite—star charts of the twelfth-century sky, and a dense field of dried vines encircling the choir and enveloping at its center an illuminated book, like the one held by the effigy of Eleanor. ”

François Réau (FR): “For Fontevraud I make an installation; I talk about the history, about the legend—the Plantagenet saga crosses eras and beliefs.”

The Plantagenet saga begins with its dynastic founder, Geoffroi le Bel, a twelfth-century count of the Angevin Empire. His son, Henry II, would marry Eleanor of Aquitaine and the family would become great patrons of Fontevraud. Here François shares the origin myth of the Plantagenet name.

The founder of the dynasty, Geoffroi le Bel, a learned prince, traveled through his domain in Angevin lands to measure their extent. And on a fantastic ride in the forest of Moulière, he meets a unicorn with the face of a woman, dressed in a golden cloak. She disappears the moment he approaches her, and the cloak she wears falls. The moment it touches the ground, it transforms the field into broom. Because of this vision, he decided to plant broom on his lands. So the name of Plantagenet comes from this plant, and the name of the dynasty is forever anchored in the marvelous. And Réau drew the name of his installation, Mirabilia, from this legend.

FR: “And the work speaks of a landscape, this landscape. It's a poetic vision, but also of the history of the Plantagenet relationship with Fontevraud. So I wanted to approach Fontevraud with a lot of feeling because sometimes an artist has an intuition, a feeling of something, but he cannot explain why. It was very important for me to capture the vibration of the Abbey of Fontevraud. It's a feeling that the religion is very important. And the landscape, too, because the saga of Plantagenet chose this place, I think, I'm not sure but I think that, chose this place because of the light and the element of the nature. Because there is something very important about the community of Plantagenet. It's a quiet place for, you know, after the war, for many things it's very important to be quiet with the meeting of nature.”

“For many things it’s very important to be quiet with the meeting of nature.”

Réau’s installation is a symbolic conjunction of clouds, stars, and vines. He shares why he chose those elements and materials.

FR: “It is my experience of the landscape, and my treatment of the landscape that led me to propose the installation of plants—the vine branches. For me, the vine evokes the cycle of the season, and the passing of time, the passing of history. This plant composition immutably inscribes the primitive and original metaphor of the dynastic plant in historical legend. So I want to use the vines to create another landscape, and the assembled vine branch are like thousands of little pencil lines, as if I had drawn this landscape in space.”

When entering Grand Moûtier, it was difficult to tell whether Mirabilia was a spiritual piece, an art piece or a kind of performance. It was ultimately all of those things. And while not explicitly religious, the vast cloud suspended in the choir of the Abbey was sublime. The starscapes installed nearby were also constellated with meaning, referencing both the cosmological and historical.

FR: “It's another part of my work, very important. It's drawing but not simple drawing. This is a Fontevraud sky map of the May 21, 1154—the night when Henri II Plantagenet, King of England, first met at the Abbey his aunt, Mathilde of Anjou, second Abbess of Fontevraud. For make this drawing, I worked with an observatory, a French observatory, which carried out astronomic calculations of what the starry sky was when Henri II visited Fontevraud for the first time. I think it's very important to talk about this piece because in the same way that all the beings who passed through Fontevraud looked at the sky at night and saw the stars and the moon, like you said—and this night of 21 May—as we ourselves are doing today. I think it's not a contemporary vision. All the people in the past see the sky, see the moon, and all the questions about, I think, it's the same questions facing time, space, and cosmos.”

When we return, we meet Martin Morillon, who is beginning to write Fontevraud’s next chapter. We learn about the new modern art museum within its walls. And hear women's voices return to the cloister.

In 2020, a new director took the helm of Fontevraud. Martin Morillon, an arts leader with an esteemed history in French cultural heritage, will help write the Abbey's next chapter. This spring, he’ll also launch a new jewel of a modern art museum, comprised of a collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century French paintings, drawings, and sculpture from the collection of Martine and Léon Cligman. Works by artists like Corot, Degas, and Soutine will be exhibited in the Fannerie, the eighteenth-century former stables of the abbesses. The museum will be led by Dominique Gagneux, who comes to Fontevraud from the Musée d’Art Moderne Art in Paris. But Morillon, who is also a vocalist, is also revitalizing another art form.

Martin Morillon: “This major monument for me is the place of knowledge, it is the place of history and we’re continuing to write this history with artists. So in a way, we're continuing this intellectual and artistic life in the Abbey now. And we are developing another way to welcome artists—with vocal art. In Fontevraud, it's natural to sing. We have two chapels, the main one, the abbatiale, the main church, and we have Saint Benoit chapel, it’s a small chapel, just behind the main church. Marvelous place, absolutely marvelous place, with special acoustics, and we have two refectories with special acoustics as well. We have an ancient dormitory with another acoustic again, and we have special places in the gardens with another acoustic. So all the special acoustics we have are very, very important for vocal arts.”

This past winter, Morillon and Fontevraud Artistic Director Emmanuel Morin commissioned composer Kerwin Rolland to create a vocal piece. Rolland wrote Asters (Stars) the work’s name drawn from the asters blooming in the cloister garden. He shares, “It was a way to bring the sisters back to life.” Here we hear the fourth movement of his work, called Astrale, which summons their presence.

The last abbess to leave Fontevraud was Julie-Gillete de Pardaillan d’Antin, who in 1792, with the impending arrival of Revolutionary forces, closed the doors of Grand Moûtier, ending the seven-hundred year lineage of monastic women.

ZW: “She had to leave the Abbey. Julie of Antin understood that the nation would take the properties and that she would have to leave. And that's what she did. She is said to be the last one to leave after all the nuns and all the monks. There is a legend saying that she fled the Abbey in a carriage with a kitten in a basket disguised as a peasant, by the tunnels of the Abbey. It is a legend. What we know is that she finished her life in poverty in Paris, in a hospital in Paris. No one knew her, she had no money. And she finished like that.”

Already ripening barberries grow red,

the ageing asters scarce breathe in their bed…

Who is unable now to close his eyes..

…in the darkness of his soul will rise

- Rilke, Book of Hours

The stones of Fontevraud always echo with the meditations and music of poets, painters, and singers. You can learn more about their work, see images, and read this episode's transcript on our website, thealcoveproject.com where you could also find the Alcôve Journal, where we post additional stories related to our current episode.

Alcôve’s editing and sound design is by Jim McKee. I'm Alisa Carroll. Thank you for listening.

Alisa Carroll

Producer and Host

Jim McKee

Sound Design and Mixing

Band of Skulls

Theme Music

Music from the Episode

“Kyrie: Orbis Factor”

The Gradual of Eleanor of Brittany Plain-chant and polyphony from the 13th & 14th centuries

Performed by Ensemble Organum at Fontevraud Abbey

Marcel Pérès, artistic director

"Astrale"

Asters

Performed by members of Musique Sacrée à la Cathédrale de Nantes at Fontevraud Abbey

Kerwin Rolland, composer

kerwinrolland.com