The Sublime Sea

Musée de la Vie Romantique | Museum of Romantic Life

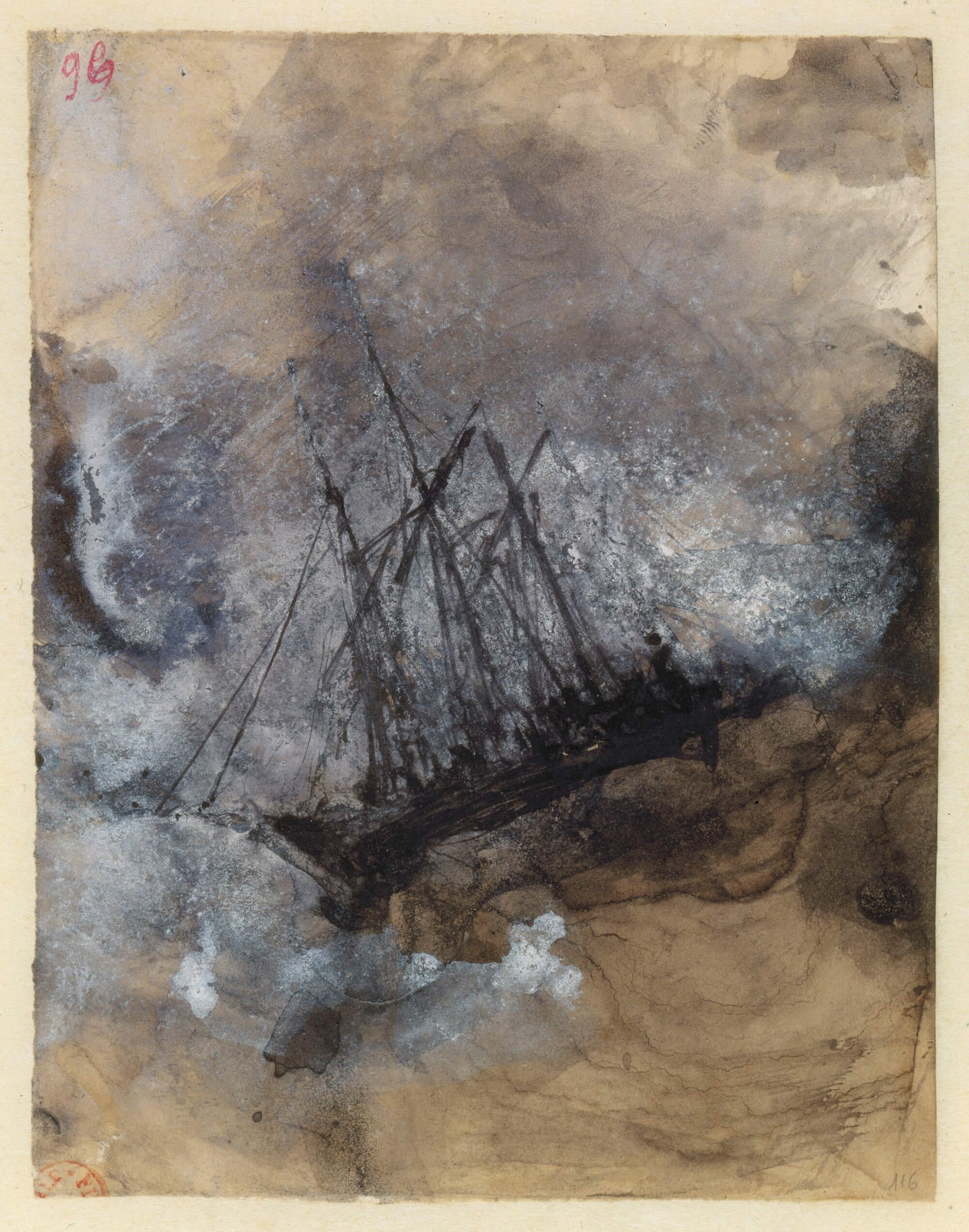

Victor Hugo, Les Travailleurs de la mer: Naufrage (1864 - 1866) © Bibliothèque Nationale de France; Louis Garneray, Le Naufragé (c. 1800) © Musée des Beaux-arts de Brest; François Nicolas Feyen-Perrin, Après la tempête (1865) © Musée des Beaux-arts de Rennes

In this time of sea change, I wanted to look at the ocean. The ocean as an expanse across which we can extend and stretch ourselves. In the midst of our current global tempests, we spoke with Gaëlle Rio, director of Musée de la Vie Romantique / Museum of Romantic Life, and curator of Tempêtes et naufrages / Storms and shipwrecks. The exhibition explores the sublime in all its terror and divinity through works by Gericault, Vernet, Courbet. Here, Rio shares her time with us to talk about atmospherics, marine landscapes, Victor Hugo, Michelet, and the light one hopes to see at the end of the storm.

GR: This exhibition is like the summary of my interests in the heritage and in the art. My first interest about the sea, and a second interest about the 19th century, and more particularly about Romanticism.

The Romantic Age began in the late 18th century as an emancipatory literary and artistic response to the rationalism of the Age of Enlightenment, emphasizing individual expression and the veneration of the natural world. One of its core tenets is the concept of the sublime, articulated by English philosopher Edmund Burke as a state of overwhelm in the face of natural forces, both terrible and godlike. An immersion in a sense of awe.

GR: Yes I love this idea of sublime. Because it's very strong in the 19th century. It was an inspiration for many artists, many painters, many writers, many musicians. The tempest, the storm, was in this idea of the sublime.

And in the exhibition I tried to make feel very ambivalent sensations. Because it's the sublime--the sensation of the fear, of the dread, of death. Because in the sublime we have fascination but we have the death.

For the exhibition catalogue Rio contributed the essay “Avie de tempête” / “Storm warning,” in which she explores how artists of the Romantic age rendered the sea and its storms as projections of their own inner landscape. Here she shares how that perspective takes shape in the symbolism of the exhibition.

GR: The storm, the mythological storm, is like a mirror of the internal storm, of a psychological storm. I love this idea because Rousseau, Jean Jacques Rousseau—his memoir Le Promeneur Solitaire told the same idea, in French, of le moi meterologique, the parallel between the feelings of the artist and the exterior elements.

One of the most powerful translators of the voice of the sea, both in text and image, was Victor Hugo. And though his visual art isn't as widely known, he created an extraordinary body of mysterious and passionately expressive works on paper.

GR: He was a fabulous writer but he was a drawer. We exhibited in the exhibition three drawings by Victor Hugo. Victor Hugo was named l’homme océan, the ocean man, because he lived in exile during twenty years in Jersey, then Guernsey. The most part of his work, his work of drawings, his work of novels and poesie, was inspired by his contact with the sea.

Victor Hugo lived in exile for nearly for twenty years for his support of democratic and revolutionary ideals. He lived in the channel islands between Britain and France, first on Jersey, then on Guernsey. On Guernsey he lived in Hauteville House atop which he built a conservatory, a room of glass where he wrote many of his masterworks, a place of both distillation of cosmic forces and expansion out into the sea and sky.

GR: Yes the parallel between a ship in the storm and his destiny, it's like Chateaubriand. A ship in the storm was like a metaphor of the destiny of an artist. And I think this image is very strong to understand the Romanticism I think.

In closing, we asked Gaëlle Rio if she would read a passage from her exhibition essay, quoting 19th century historian and writer Jules Michelet.

GR: Jules Michelet was an author, and he inspired the concept of the exhibition for me. It’s a very important author about he sounds of the storm.

“Bien avant de voir la mer ; on entend et on devine la redoutable personne. D’abord c’est un bruit lointain, sourd et uniforme. Et peu à peu tous les bruits lui cèdent et en sont couverts. On en remarque bientôt la solennelle alternative, le retour invariable de la même note, forte et basse, qui de plus en plus roule, gronde.”

“Long before seeing the sea; we hear this formidable being. At first it is a distant noise, dull and uniform. And little by little all noises yield to it and are drowned out. We notice the solemn alternation, the invariable return of the same note, strong and low, which rolls more and more, roaring.”

The exhibition Tempêtes et naufrages, is now closed, but on the website of the Musée de la Vie Romantique you can order the catalogue, in French, view images, listen to music, video and more. vieromantique.paris.fr

To learn more about this episode, you can view images, read the transcript, and see more on our website, thealcoveproject.com

Alcove’s editing and sound design are by Jim McKee with assistance from and additional music by Emma Jackson.

I’m Alisa Carroll, thank you for listening.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Alisa Carroll

Producer and Host

Jim McKee

Sound Design and Mixing

Band of Skulls

Theme Music

Music from the Episode

Patrick Watson, “Je te laisserai des mots”

NIN, “La Mer”

Emma Jackson, “The Light”